Here’s a bold prediction: the election of Donald J. Trump as President of the United States will, at worst, leave the environmental movement unaffected — and may actually improve its prospects in the long term.

Anyone who knows me personally or has followed my social media knows how vociferously I opposed Trump’s election, for profligate reasons — not the least of which being his denial of climate science and avowal to dissolve our climate commitments, such as our intended nationally determined contribution to the COP21 Paris Climate Accord (which took the form domestically of President Obama’s signature Climate Action Plan), and our bilateral agreement with China to co-lead on decarbonization between presidents Obama and Xi.

But I’ve always been an eternal optimist, and as I try to accept our new post-Trump reality, I can’t help but look at our brave new world as not a crisis, but an opportunity.

First, some reality checking. I was in Paris for COP21 and cannot underestimate the groundbreaking nature of the Agreement and all that entails. President-Elect Trump has said he will abrogate our Paris commitment, but President Obama has already made the US a signatory; now that the Agreement has entered into force (as of 4 Nov 2016), no country can withdraw from it until it has been in force for 3 years. After that, withdrawal requires a one-year notice. So, the earliest that the US can withdraw is Nov 4, 2020 — by which time the American citizenry will have already decided whether we’ve had enough of President Trump.

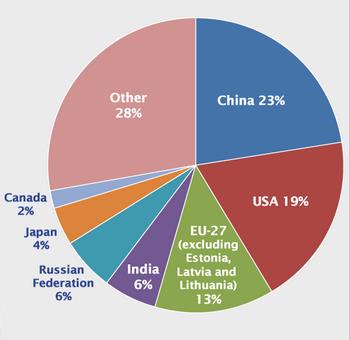

President Trump can, of course, simply kill the Clean Power Plan and all US efforts to reduce our greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, even if we’re technically still in the Paris Agreement. The Clean Power Plan focuses its regulations on coal-fired power plants, which are responsible for 31% of US GHG emissions; President-Elect Trump has already pledged friendship to the coal industry and stated plans to open more wildlife areas to oil and gas exploration. But regulation isn’t what’s depressing coal power; the industry has been in decline based on simple economics. Conventional coal plants cost $95 per MWh in 2015, even without the carbon capture and storage requirements that would add another $50/MWh. In contrast, a megawatt-hour of geothermal electricity cost $47; onshore wind, $74; conventional natural gas, $75; hydroelectric power, $85 — all cheaper than coal. Advanced nuclear power is at parity with coal at $95, and even solar photovoltaic electricity, currently priced at $125 per MWh ($114 after federal subsidies), has fallen 79% over the last half-decade and continues to fall. (Prices are given as levelized cost of energy, or LCOE, by the Energy Information Administration.)

Potentially more potent than rescinding specific environmental regulations is the prospect of eliminating or significantly gutting the Environmental Protection Agency entirely, another Trump campaign promise. Even if this were legally possible (difficult, at best) and the American public allowed it (we’ve seen bipartisan rebellion against eliminating environmental protections in the past), I might argue that this isn’t a terrible thing — if we seize the opportunity to rebuild a better Agency from its ashes.

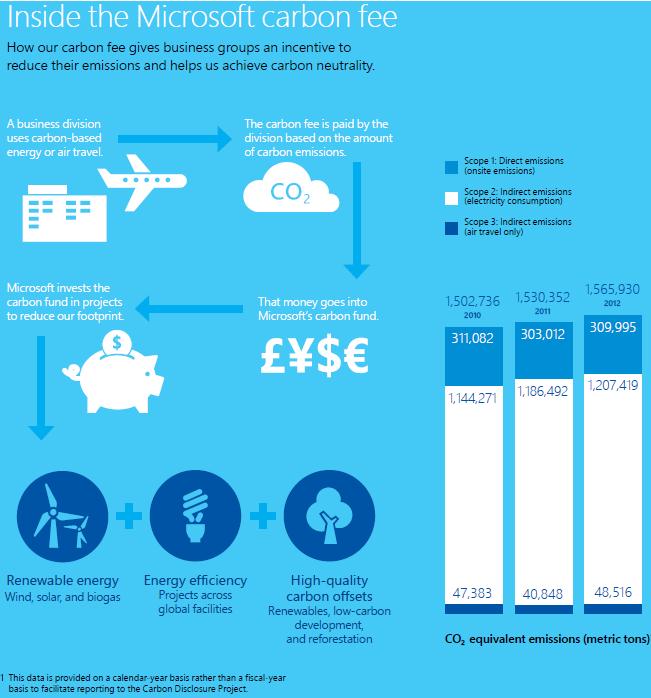

EPA was founded by Richard Nixon in 1970 as a counterweight against corporations who were despoiling the environment with impunity. Its early regulations were designed to keep rivers from setting ablaze, literally and figuratively — certainly good things. But society’s relationship with corporations has changed. Many corporations now see investment in our country’s social and ecological fabric as a good long-term investment (see Andrew Winston’s latest book The Big Pivot for an in-depth explanation). We no longer need counterfactual, end-of-tailpipe regulations to advance corporate sustainability; doing less bad is no longer enough. We need to reformulate the rules of the marketplace itself, and then let business do what business does best: innovate.

It’s not like EPA hasn’t changed with the times. Acting on a recommendation by the Environmental Defense Fund, George W. Bush’s EPA scrapped a proposed counterfactual regulatory scheme to curb acid-rain causing sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions, and instead enacted a cap-and-trade mechanism that decreased SO2 emissions by 36% even as electricity generated by the affected coal plants rose by 25% — and at a cost savings of 15-90% less than the expected costs of the original regulation. The Economist called this “probably the greatest green success story of the [1990s]”.

Still, this hasn’t led to success on similar market mechanisms, such as carbon pricing (despite calls from companies ranging from Patagonia to ExxonMobil for a price on carbon), or better valuation of natural capital. Perhaps we need to go back to the drawing board to design an agency that can work with progressive businesses to define the rules of a clean economy. Let us use the discontinuity of this administration to lurch forward, not backward, in the way we rebuild our new economy.

As folks smarter than me have already argued, the sustainability movement has enough momentum to survive President Trump. I view this period as the dot-com winter of the 2000s: a harsh testing grounds for truly sustainable models. Strong models like Amazon and Google survived that testbed, and similar resilient models will outlast this sustainability winter. Let’s be poised and ready to lead once the spring blooms.